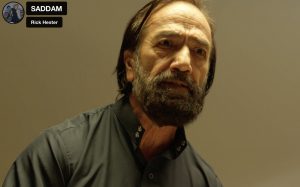

Interview | Saddam

Movie Name: Saddam Director Name: Rick Hester

Hello Rick! Welcome to SIFF

1.The movie Saddam is definitely a great story. What made you come up with this idea?

As I read the transcripts of their declassified conversations, the bond that was developing between this young FBI agent and Saddam was just so compelling. It was a great story. And one that virtually no one had heard about. Here you had this young U.S. government employee, Agent George Piro, born in war-torn Beirut, but raised in California, and Saddam, isolated inside an American detention center, and somehow these two find a way to connect on just this very human level. Yeah, it was unexpected. And the stakes for both were really so high. It also helped that Saddam, when recalling these old stories to Agent Piro, stories full of intrigue and deception, would always end the story with something like, “It was just like in the movies.” So it wasn’t a huge leap.

2.Why did you choose this sensitive topic?

I came away from reading the transcripts believing that had there been just one bridge of trust, one channel of honest contact between the U.S. government and Saddam, the entire catastrophe of the Iraq War may have been avoided. In other words, in a world where powerful centrifugal forces seem to be collapsing bridges of trust, pulling societies, alliances and global institutions apart in their wake, SADDAM is a story that reminds us of the vital importance to the world of building bridges. In this case that process began with two people engaged in simple conversation.

3.Do you think Saddam deserved a second chance?

I think that’s a very interesting question. I’d be very curious what the Iraqi people would say about that today. Someone should take a poll. I do think that this story probably reveals a side of Saddam that even many Iraqis didn’t know existed.

4.What are your ideas on redemption?

Redemption requires one to atone for what one views as a mistake or a fault. In Saddam’s case, I don’t think he believed atonement was required. He just didn’t see his role in history that way. In fact, he’s quite unapologetic. It’s only when his more self serving narratives are challenged that you see any hint of discomfort or remorse. At one point in the transcript he’s questioned about his rumored involvement in the murder of a close friend whom he’d begun to perceive as a political rival and he becomes very upset and ends the session. Later he explains to Agent Piro that he was never upset with him, “It was just that some things in the past are dark.” That’s really as close as he gets. Saddam truly viewed himself as a revolutionary and his actions as always necessary to further his pan-Arabist vision.

5.How do you see the friendship between the FBI agent and Saddam?

I think it was genuine. But I also think it was complex and driven by strong, practical motivations on both sides. While Agent Piro certainly had some very high-level and specialized experience inside the FBI – he had been behind the “Phoenix Memo” warning that Bin Laden was focusing student terrorists on civil aviation schools, and he was also a member of CTORS, the FBI’s rapid response terrorism fly team – never-the-less, he was just a field agent. And this was a mission with enormous stakes. He didn’t want to fail. On Saddam’s side, he cared deeply about how history would view him. Engaging with the U.S. government in these interviews was perhaps another way to try to shape those perceptions. But also, Saddam truly began to see “George” as a son. “As a father wishes a son to be successful, George, I wish for you to be successful,” he says late in the transcripts. I think the deeper reason that Agent Piro’s time with Saddam was later seen as such a success was that Saddam became so emotionally dependent on him. And that was at least partly by design.

6.How do you think the audience is going to perceive this story?

I certainly hope the audience sees this film as a story about people and not about politics or any kind of political narrative.

7.Saddam created havoc. Yet you have portrayed him like a human. What made you look at Saddam from such a humanistic perspective?

Saddam Hussein strode the world stage for decades. On television, he was a fixture in America’s living rooms for a good part of that time. We were engaged in our second conflict with him. And the so-called “Butcher of Baghdad” was someone most Americans felt they knew. And yet when The New York Times was the first to publish a story detailing his new life inside an American detention center, they reported Saddam spent most of his time tending to a courtyard flower garden and writing poetry. That was a Saddam I certainly hadn’t imaged. So that was where the germination began. But once I began seriously considering writing the screenplay, it became very important in my mind to strike the right balance so that SADDAM wouldn’t be perceived as a ‘sympathetic,’ or revisionist, portrait of a former dictator. My solution was to include in the screenplay excerpts from a powerful series of Human Rights Watch interviews conducted in 2004 in Baghdad. In them the rights group documents the stories of the Kurdish and Shia survivors of Saddam’s crimes. And I think with them included I was able to find that balance.

8.As a director, how challenging was this project for you?

This was my first directing project, so in those first hours I was just learning the rhythms of a set and exactly how to get camera and sound rolling, and just all of it. And it was all a bit overwhelming. However, the one source of calm I found, at the center of all of it, were the actors. We began the shoot with the Human Rights Watch monologues I just mentioned. The calm I found was in that space where there was just me and the actors. Where cinema is created. I was so blessed that those first scenes each featured truly extraordinary performances. The material itself is searing. So the challenge for me, once we got moving, became to then find the language I would need to sculpt the actor performances, to make all those slight adjustments you need to make to find the performance you need. And I found the skills you develop as a writer really come into play here. As a writer you’re language is pretty precise. And you’re also used to trying out several different ways to communicate something. Eventually you develop a common language with an actor and it works. Also, surprisingly, pacing was one thing that was a consistent challenge. I had a feel for what the pace should be inside the scenes and I didn’t always feel that we were there. So what I wound up doing was I’d just say lets stop and do three quick speed rounds of the scene just to build up some muscle memory. Unknown to them, we’d keep rolling. And we nailed the scenes.

9.What message do you wish to send to the world through this movie?

As time passed and Saddam’s life neared it’s end he came to truly trust “George” as we’ve discussed. The bridge of trust the two had been working on was complete, and the revelations that followed were stunning. Saddam’s true WMD motivations. The tragic missed messages on both sides. The deceptions. But by then, it was all too late. We live in a world that is once again becoming defined by spheres of influence, military blocs and trenches. A world in retrograde. A world that seems headed for catastrophe. That is why I feel this story is so vital. Why I produced this concept short. And why I want to fund a feature film and bring this story to audiences around the world. It’s a story that serves as a handbook to the vanishing art of building bridges. Bridges that lead to trust. And trust is always at the heart of any peace.

10.Are you planning for your next project? And is the topic going to be as intriguing as this one?

I have to be honest, I have read every letter and email publicly available that Osama bin Laden wrote in Abbottabad before he was killed. There’s very probably a LETTERS FROM ABBOTTABAD coming. There’s also a great book I read a few years ago called CHIEF OF STATION, CONGO, by Larry Devlin. Devlin was the CIA’s chief of station in Congo during a time when the country was at the strategic heart of the Cold War chess match the U.S. and the Soviet Union were engaged in. And with truly terrible consequences. But first of course there’s SADDAM the feature film!

11.We absolutely loved this movie, Saddam. I hope you enjoyed working with SIFF!

I’ve absolutely loved my experience with SIFF. What a lot of fun. SIFF truly loves film and works very hard to recognize and support emerging filmmakers. So thank you for that support.

The post Interview | Saddam appeared first on Swedish International Film Festival.

214